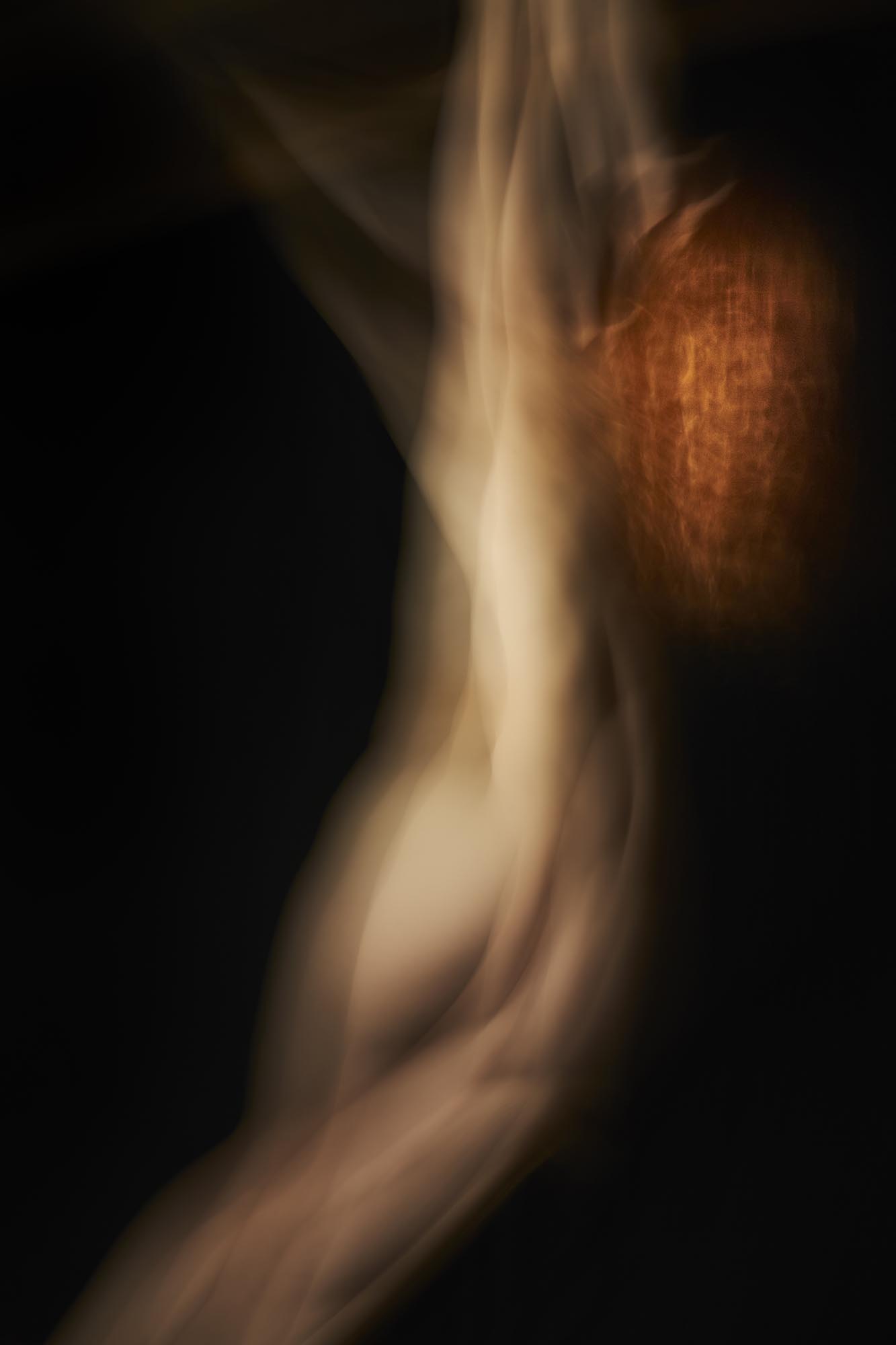

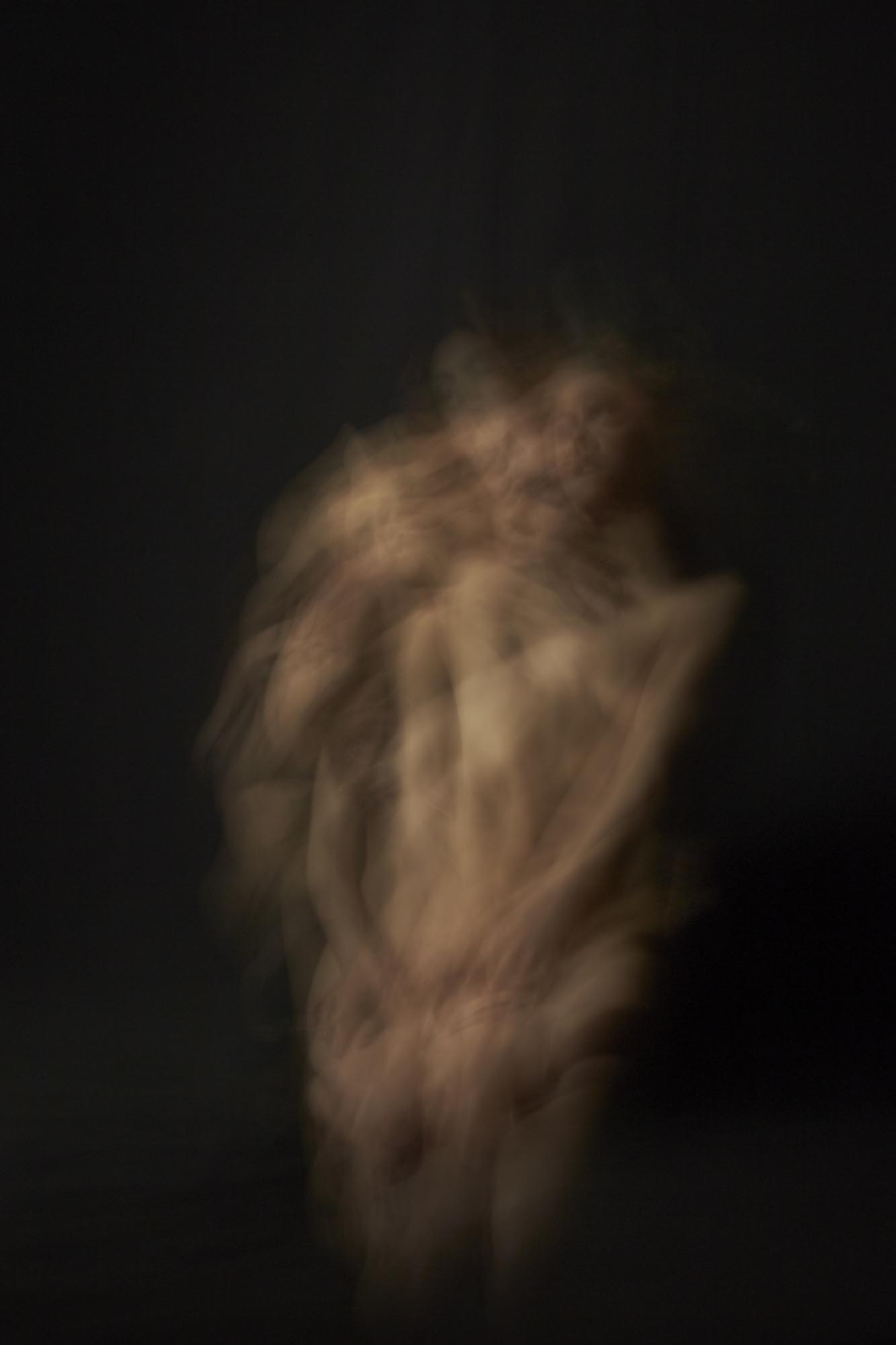

Ishtar, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, Ed.1/6+2PA

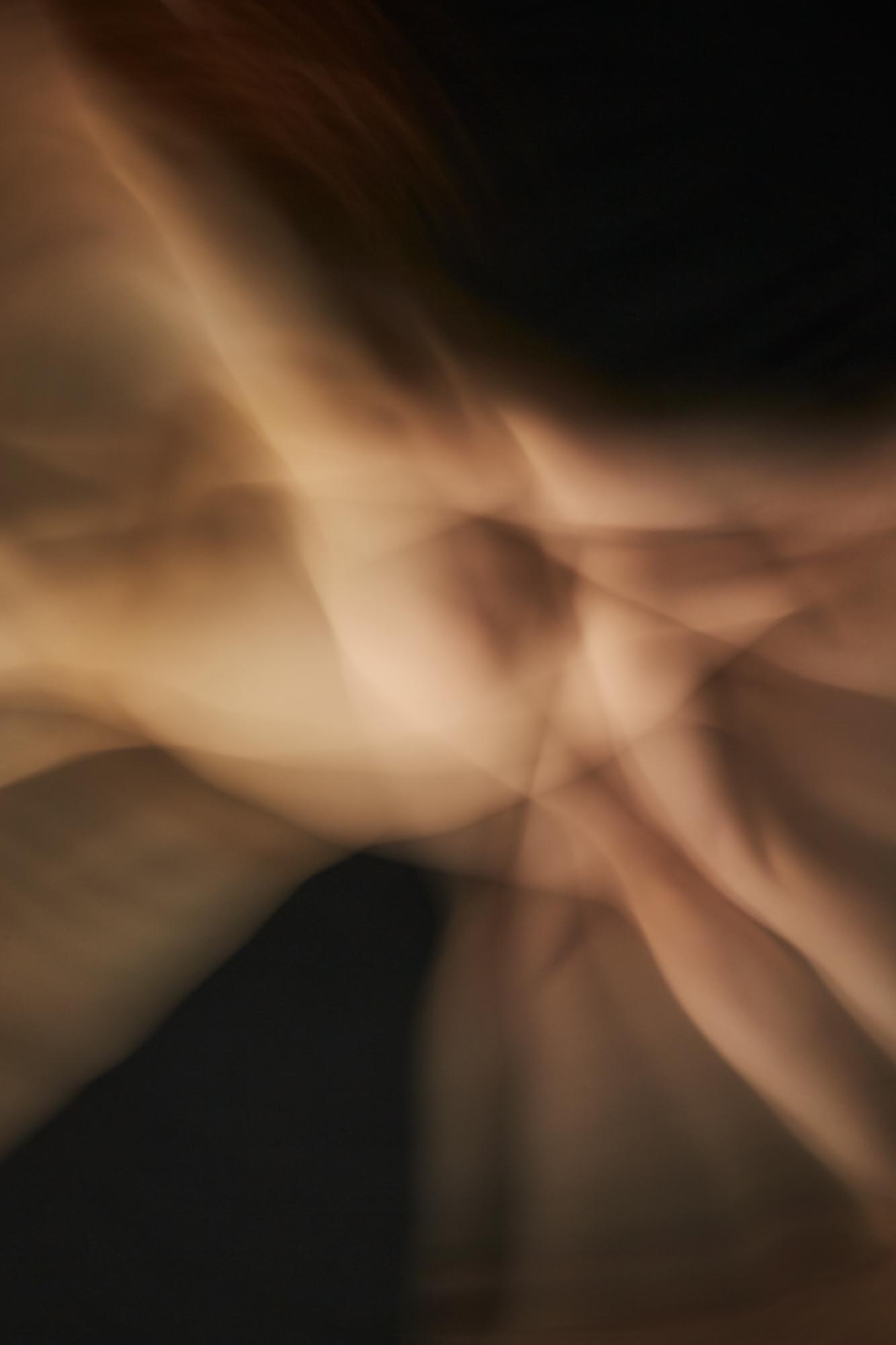

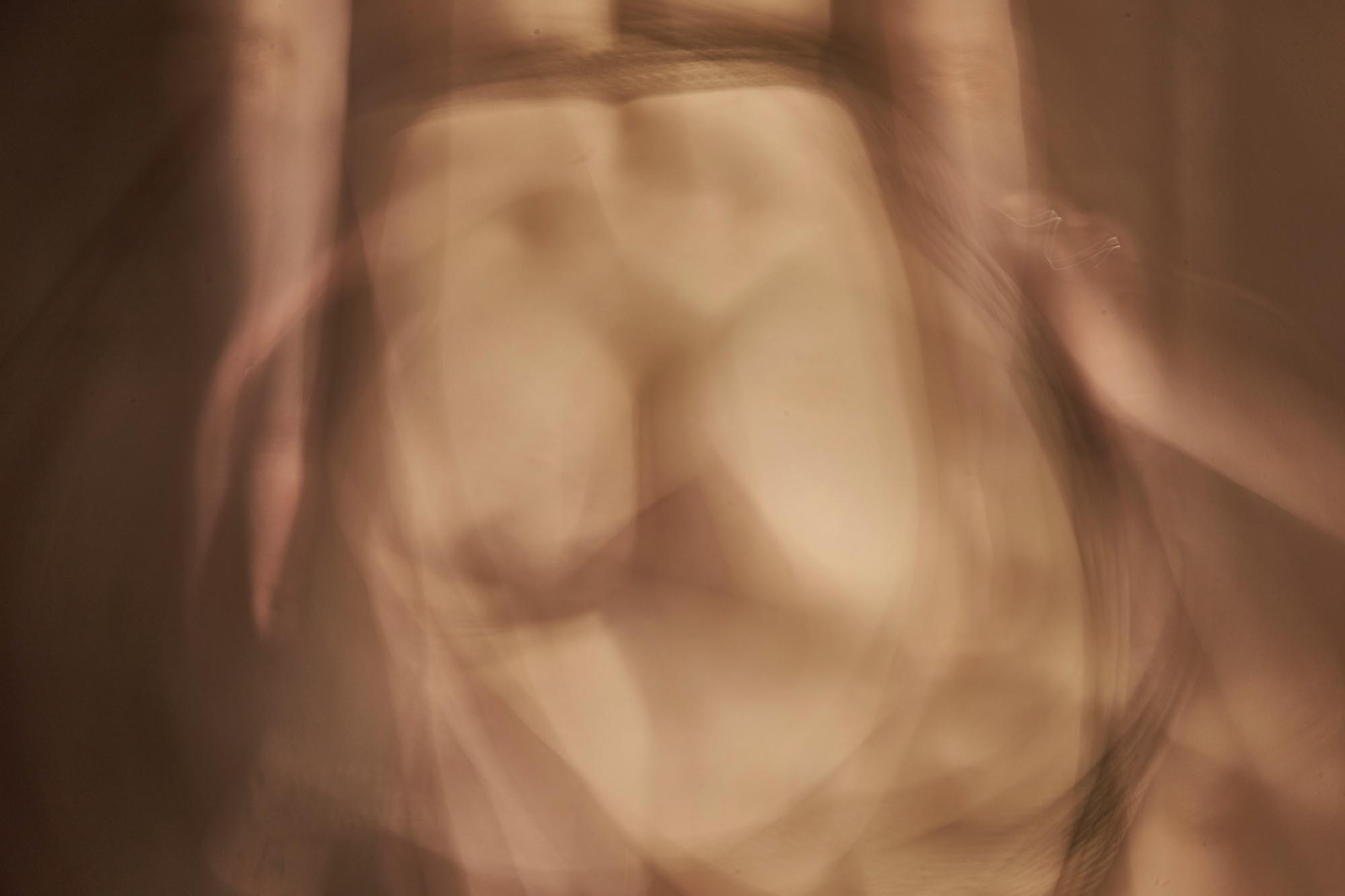

Anasyrma, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

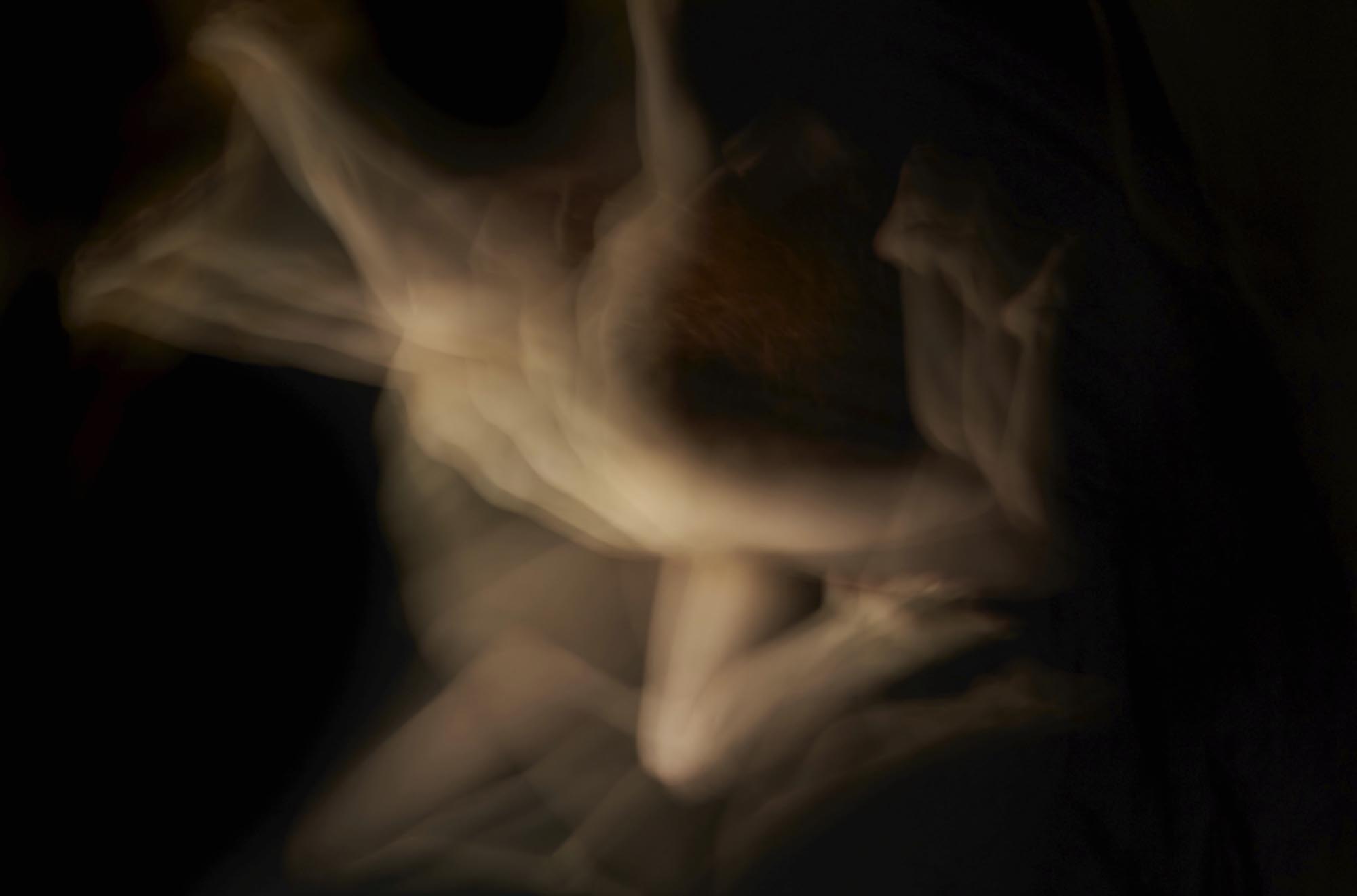

Sorgente, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

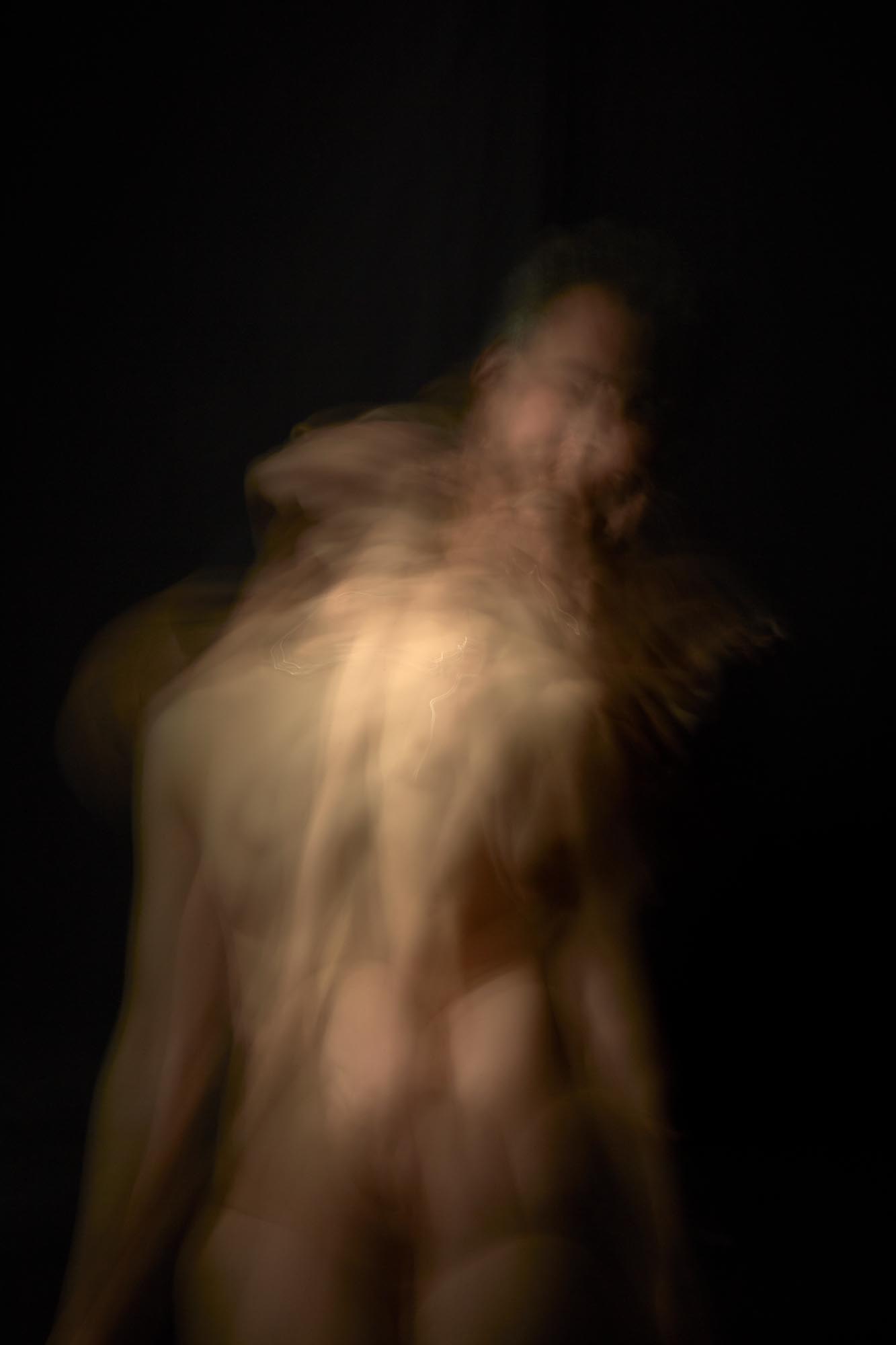

Apotropaico, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

Callipigia UNO, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine art, 150X100 cm

Callipigia DUE, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine art, 150x100 cm

Ciprigna, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

Danza di Ishtar, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

Donne Senza Titolo, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

Hera Rapita, 2017, stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Hera Esiste, 2017, stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

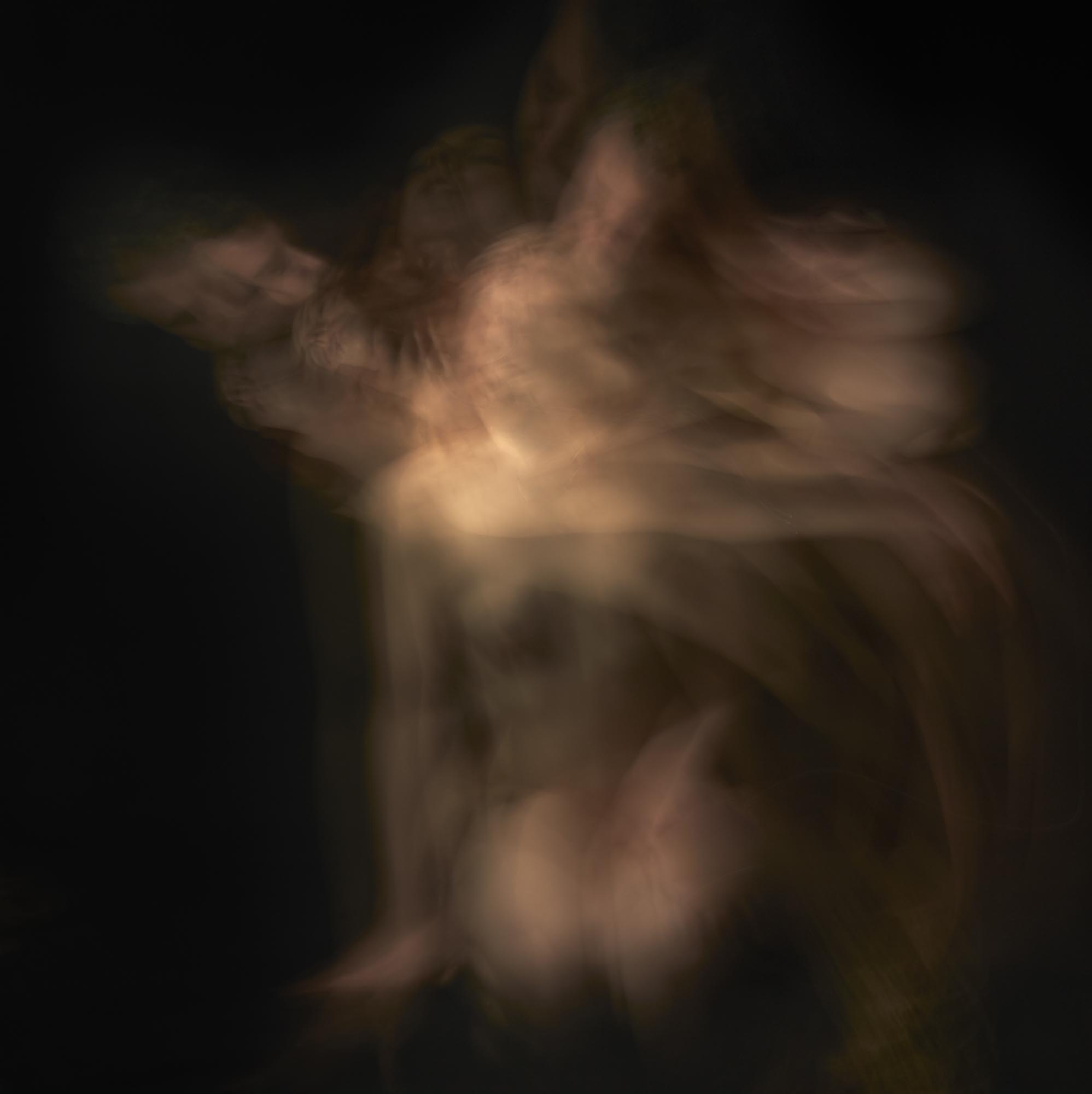

L'ira di Hera, 2017, stampa su Carta Fine Art, 120x120 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Il Cerchio della Luna, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm

Il Sogno Pandemo, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

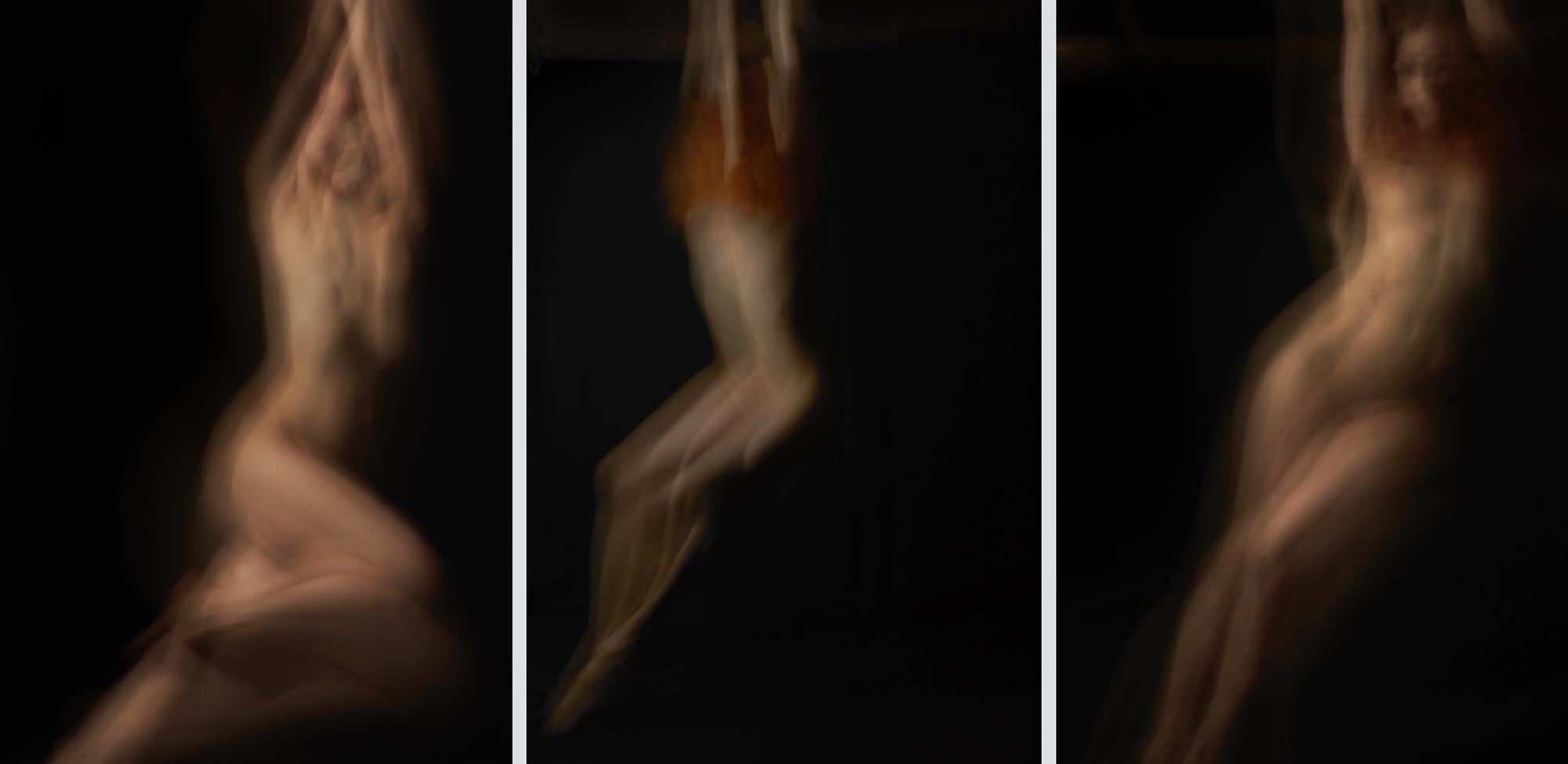

Le Danze di Erzulia UNO, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, Ed.1/9+2PA

Le Danze di Erzulia DUE, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, Ed.1/9+2PA

Le Danze di Erzulia TRE, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, Ed.1/6+2PA

Loa, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

Nell'acqua Uno, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Nell'acqua Due, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Pandemo, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Papaloa, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Senza Gelosia, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Pygos, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm

Eris, 2017, Stampa su carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Per Sempre Tua, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Doppio Corpo

The skin to skin intensely staged by Veronica Gaido’s shots pits the city figure against the female figure. The double-theme proposed by the photographer is, so to speak, classic. It falls within the vast repertoire of scenes developed by international photography since the mid-80s and especially throughout the 90s of the last century: a form of art

which has reached aesthetic recognition as a fundamental part of the contemporary art system. The two themes - only apparently fighting - intertwine with great strength, in a sort of osmosis, exchanging characteristics and features, which one might think to be non-transferable. The twine between the two is so strong that the metropolis is humanised, with its architecture and its skyscrapers, in a turbulent dialogue between buildings. The city thus reveals its bare, spectacular, luminous structure, where rigor aims to dissolve into a story. At the same time, women free themselves by revealing themselves in their own inner dynamism, and in turn generating through their shade the gestures, shapes, cuts and geometric evidence belonging to the volumes of a solitary architecture, or even to certain sculptures. In the transparent “daily exterior” of the cities and in the dense, shady “nightly interior” of the female nudes, the blurring, the multiplication of the image, the movement, the spirit of transformation, a calculated, methodical vision stylistically dominate. “I have some obsessions,” confesses Veronica, and I think to myself: don’t worry, you’re right. Artists choose their subject according to what most violently forces us to look at it and to represent it. Frankly, they do so with a certain obsession, investigating something, investigating that part of the world which we consider essential with that all evidence and in spite of everything; an extremely interesting research, which trespasses onto self-therapy, onto a desire for healing. While I am thinking this, she adds: “My architectures, which I once associated with Italo Calvino’s invisible cities... well, I tried to reawaken these strange animals. I picture myself as - or rather I identify with - a skyscraper: this is the fantasy; a building that will always find another skyscraper in front of itself, and afterall it is as if while facing each other they looked into each other, an easier gesture than for us humans, no? They are so similar to each other ... they are like bodies. I want my nudes to be blurry too: I try to highlight a rhythm, which for me is a constant of life, and I show a certain kind of beauty, because every body is beautiful, all that is needed is a part of it, all that is needed it a look from a certain angle ... Mine is always a spiritual journey, I am always searching for a soul within elements, whether it’s a city or a woman.” Veronica claims that an important source of inspiration for her is Futurism. It strikes me how, whatever the age, painting and photography continue to play their match - a tennis match for example – sometimes with rallies from the baseline, increasing with close exchanges by the net, in a tournament that seems to be never-ending, as it is not clear what qualities are needed to win it once and for all: precision? elegance? the speed of execution? mobility? Nothing is decisive, and the match has been going on for almost two centuries. It is interesting to observe that painting and sculpture on the one hand, and photography on the other, are capable of drawing strength from their “opposition” by mirroring and imitating each other: sublime photographers like Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson would not even shoot without having had large paintings occupying their minds for a long time.According to Veronica Gaido, the subject is alone; she herself contemplates and manipulates the image as a loneliness: she worships it, this is certain, by helping it focus on its own exclusive scene, where it is exposed but still protected. The image therefore establishes and sets the perimeter for its own setting by repeating itself. Everything here - these refracting city parts and these obscure/luminous bodies that, among the sick lights, even recall Caravaggio - seems to wriggle away, as if shaking off the banality of automatic recognition, the stereotype of the so-called guiding-images - those that are incessantly created and destroyed on the vast, ephemeral, innumerable screens of our civilisation (known as the civilisation of spectacle, but what would the spectacle be?). Taking very few pictures, this could be the paradoxical choice for every true photographer / artist within a habitat that is mad about image overdose. Through Veronica the image - put in sequence, thus obtaining

its success from a project and not from a single picture – literally seeks and finds its autonomous structure: it rotates on its own axis, so independent and pure. We see its torsion,

its irradiation, its tension towards abstract and musical worlds, its leap - a sort of dance – seemingly violating the force of gravity. The effect stems from the gesture of moving the camera wisely, like a brush, or a small video camera. The implicit lack of motion typical of every photograph appears defeated here, together with the sense of something that has already passed that accompanies it. Yes, an image searching for life is everywhere, a vision that is never still, without peace, momentarily stuck in a structure full of glare. Is it the feeling of an expanding sound? It is the shape, and its echo.

Marco Di Capua

Il corpo a corpo intensamente messo in scena dagli scatti di Veronica Gaido costringe a un bel match la figura della città con quella della donna. Il doppio tema proposto dalla fotografa è per così dire classico, sta in cima a quel vastissimo repertorio di scene che dalla metà degli anni Ottanta e soprattutto lungo tutti i Novanta del secolo scorso è stato sviluppato dalla fotografia internazionale, giunta nell’epoca della sua riconoscibilità estetica come parte fondamentale del sistema dell’arte contemporanea. E tanto i due temi, che solo apparentemente combattono, si intrecciano in una specie di osmosi, rilasciando l’uno all’altro caratteri e proprietà che credevi incedibili, che la metropoli, con le sue architetture, i suoi grattacieli si umanizza in un turbolento dialogo tra edificio ed edificio, svelando la sua struttura spoglia, spettacolare, luminosa; mentre la donna si libera mostrandosi nel proprio intimo dinamismo, e generando nell’ombra, a sua volta, i gesti, le forme, i tagli e la geometrica evidenza dei volumi di un’architettura solitaria, di certe sculture addirittura. Nei trasparenti “esterno-giorno” delle città e nei densi, ombrosi “interno-notte” dei nudi femminili, stilisticamente dominano la sfocatura, la moltiplicazione dell’immagine, il movimento, lo spirito di trasformazione, una calcolata, metodica visionarietà. «Ho delle fissazioni››, mi confessa Veronica. E io penso: tranquilla, sei nel giusto, per ogni artista la scelta del soggetto ricade su quello che più violentemente ci costringe a guardarlo, e a rappresentarlo, con una certa ossessività a dirla tutta, investigando su qualcosa, su quella parte di mondo che con ogni evidenza e a dispetto di tutto riteniamo essenziale, è un’investigazione particolarissima per giunta, che sconfina nell’autoterapia, in un desiderio di guarigione. E mentre penso questo, lei aggiunge: «Le mie architetture, che una volta ho associato alle città invisibili di Italo Calvino... insomma ho cercato di animarli questi strani animali, mi immagino, anzi mi immedesimo in un grattacielo, questa è la fantasia, un edificio che per sempre troverà un altro grattacielo davanti a sé, e in fondo è come se fronteggiandosi si guardassero dentro l’un l’altro, gesto più facile che per noi umani no? Sono così simili tra loro... sono come corpi. Anche i miei nudi li voglio mossi, cerco di mettere in luce un ritmo, che per me è una costante della vita, e mostro un certo tipo di bellezza, perché ogni corpo è bello, ne basta una parte, un’angolazione... In tutto, che si tratti di città o di donne ricerco un’anima, il mio è sempre un viaggio spirituale››. Sostiene Veronica che un’importante fonte di ispirazione per lei è il Futurismo. Mi colpisce come, qualsiasi sia l’epoca, pittura e fotografia continuino a giocare la loro partita – per dire: a tennis – con palleggi da fondo campo, qualche volta, sempre più spesso con scambi ravvicinati, sottorete, in un torneo che sembra non avere fine, anche perché non si capisce che doti occorrano per vincerlo una volta per tutte: la precisione? L’eleganza? La velocità di esecuzione? la mobilità? Niente risulta risolutivo, e il match sono quasi due secoli che continua. Diciamo che è interessante come pittura e scultura da una parte e fotografia dall’altra, specchiandosi, imitandosi, siano capaci di trarre forza dal loro “avversario”: eccelsi fotografi tipo Jeff Wall e Gregory Crewdson non farebbero nemmeno uno scatto senza che grandi quadri non occupassero, da tempo, la loro mente. Per Veronica Gaido il soggetto è solo, lei stessa contempla e manipola l’immagine come una solitudine: le riserva un certo culto, questo è certo, aiutandola a focalizzare la propria scena esclusiva, là dove si espone ma è protetta: così l’immagine fonda e perimetra la propria scena ripetendosi. Tutto, qui – questi rifrangenti pezzi di metropoli e questi oscuri/luminosi corpi che un po’, tra le luci malate, sanno anche di Caravaggio – sembra divincolarsi, come scrollandosi di dosso la banalità del riconoscimento automatico, lo stereotipo delle cosiddette immagini-guida, quelle che incessantemente nascono e muoiono sui vasti, effimeri, innumerevoli schermi della nostra civiltà (detta dello spettacolo, ma lo spettacolo quale sarebbe?). Con Veronica l’immagine – messa in sequenza, ricavando dunque da un progetto e non da un singolo scatto la propria riuscita – cerca e trova il suo assetto autonomo – letteralmente: ruota sul proprio asse – la sua essenza autonoma, e pura. Ne vediamo la torsione, l’irradiazione, la tensione verso mondi astratti e musicali, lo slancio, una sorta di danza, come a violare la forza di gravità. Sì, ovunque c’è una figura irrequieta, una visione mai ferma, senza pace, bloccata per un attimo in una struttura colma di rifrazioni. La sensazione è quella di un suono? È la forma, e la sua eco.

Marco Di Capua

Veronica Gaido - Photographer