Profondità Sospese UNA, 2018, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

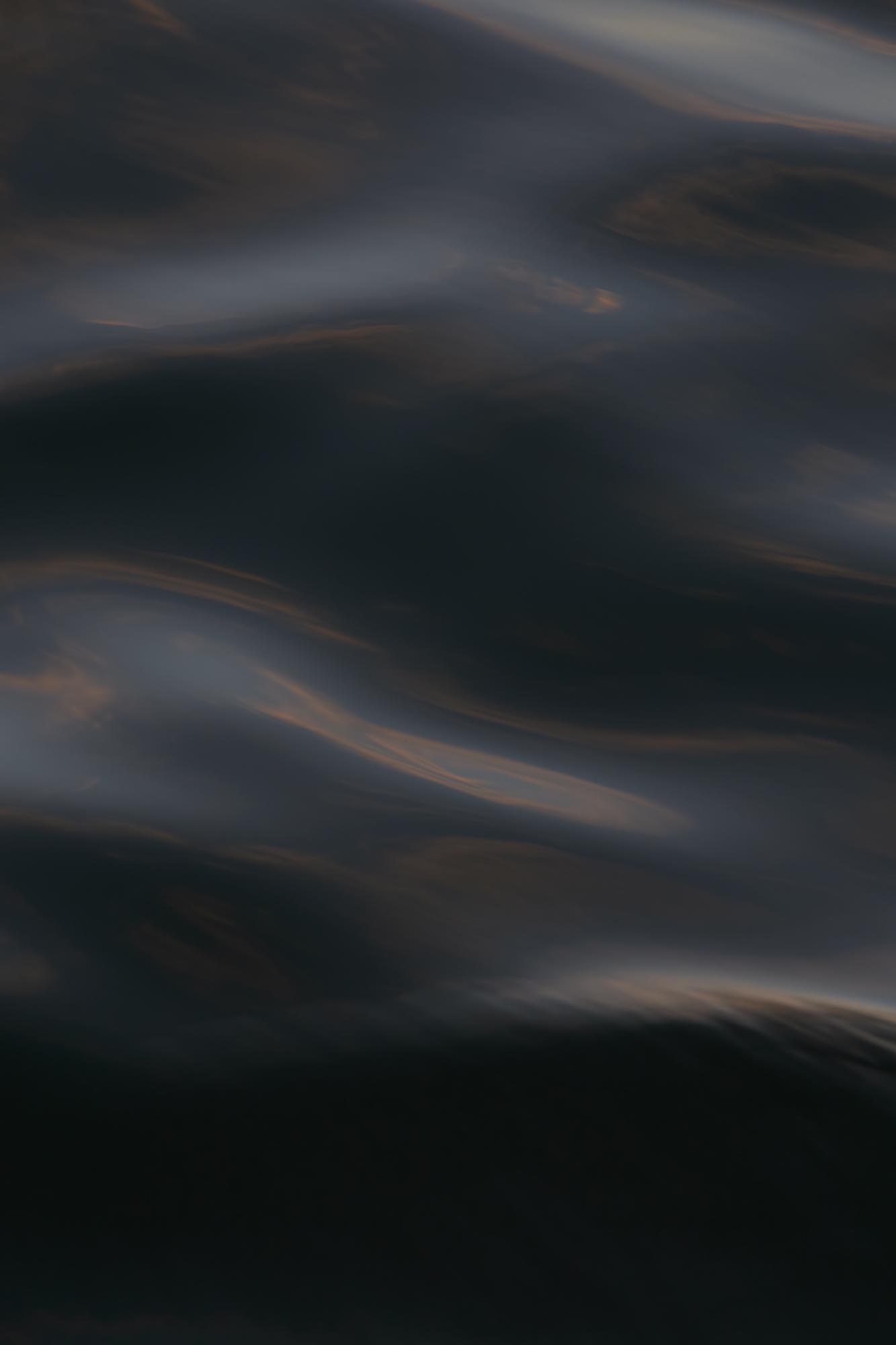

Profondità Sospese DUE, 2018, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

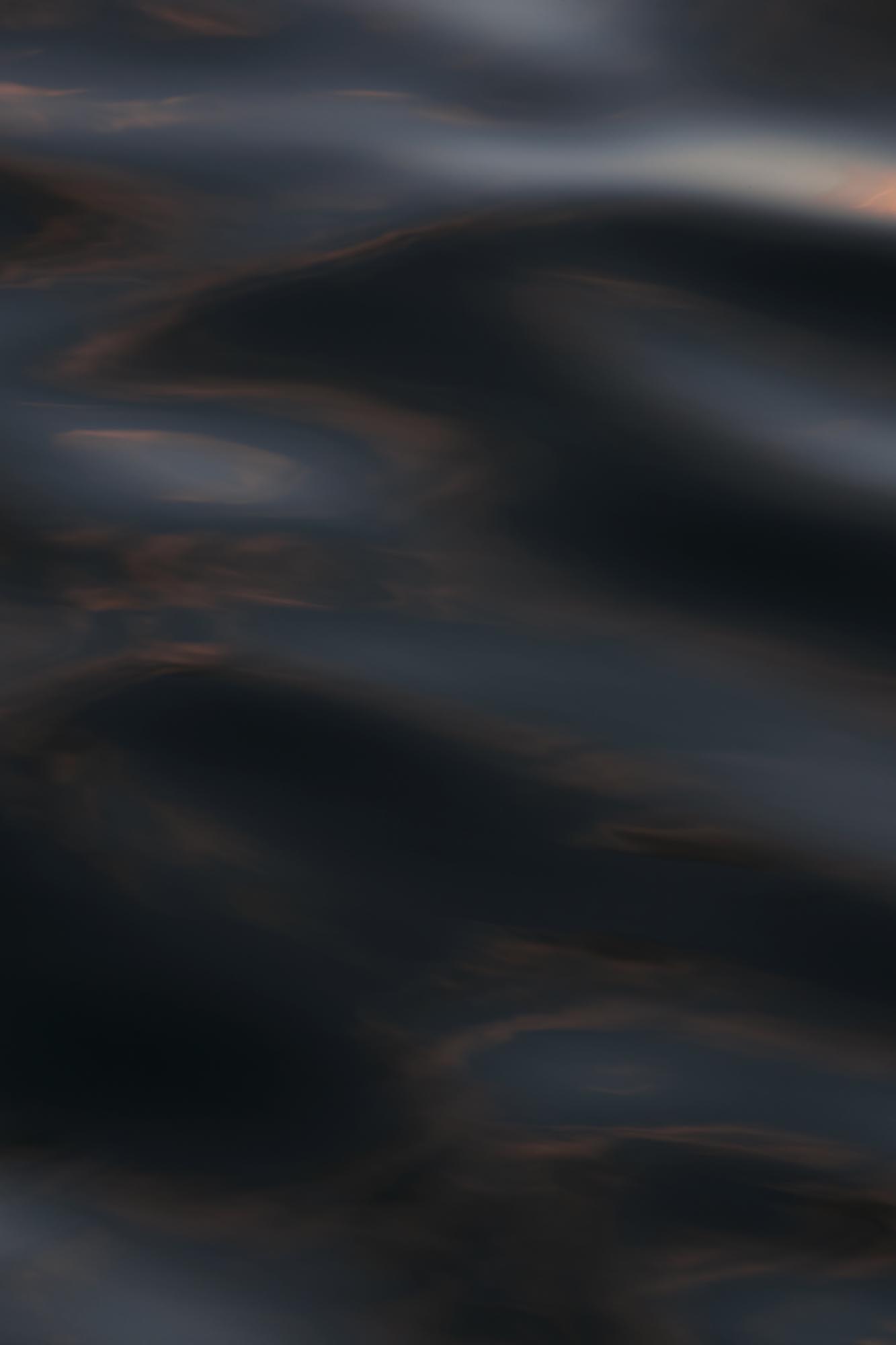

Mare Alchemico Dittico, 2018, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 70x50 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

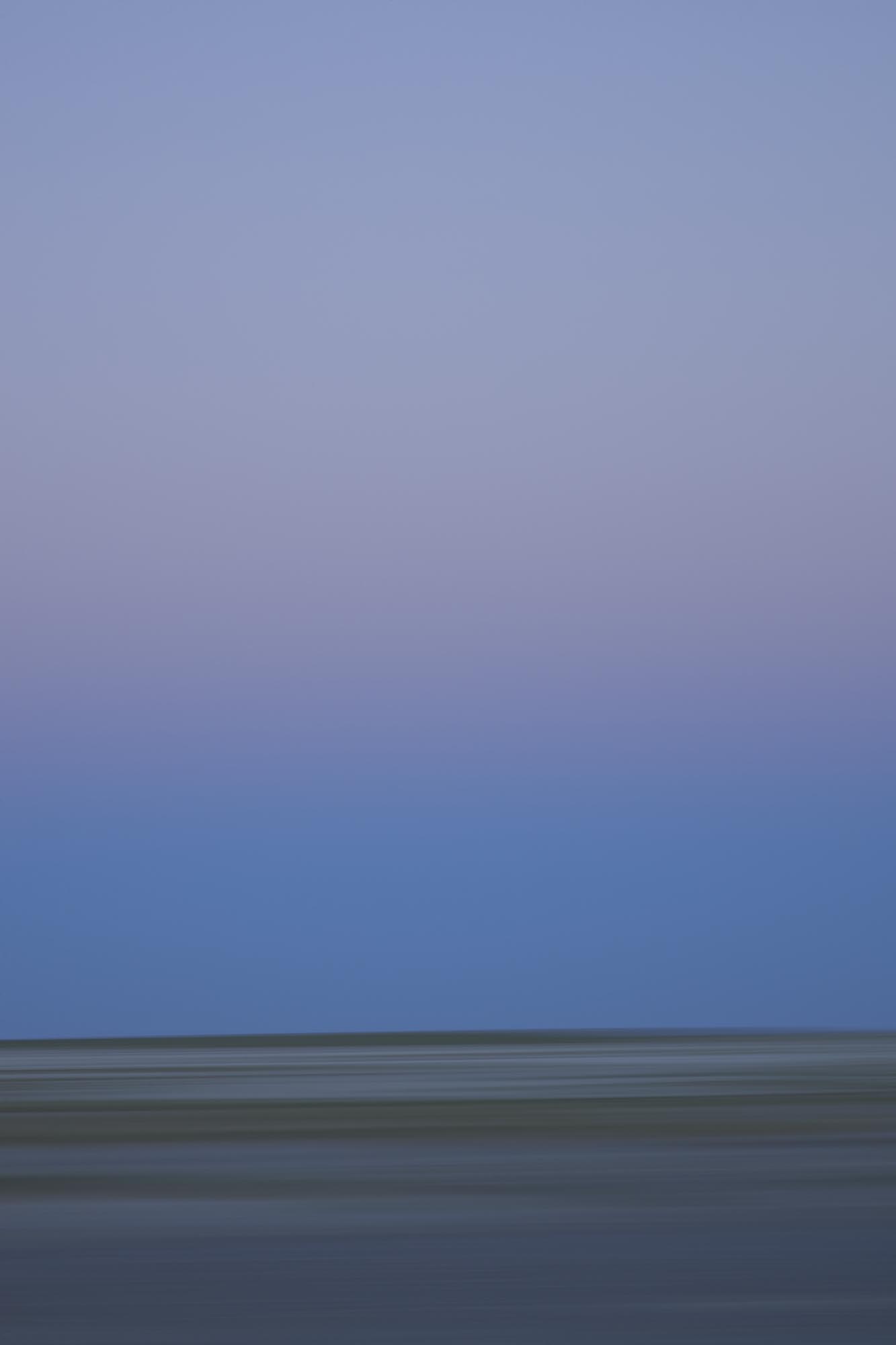

Oltre l'Acqua UNO, 2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

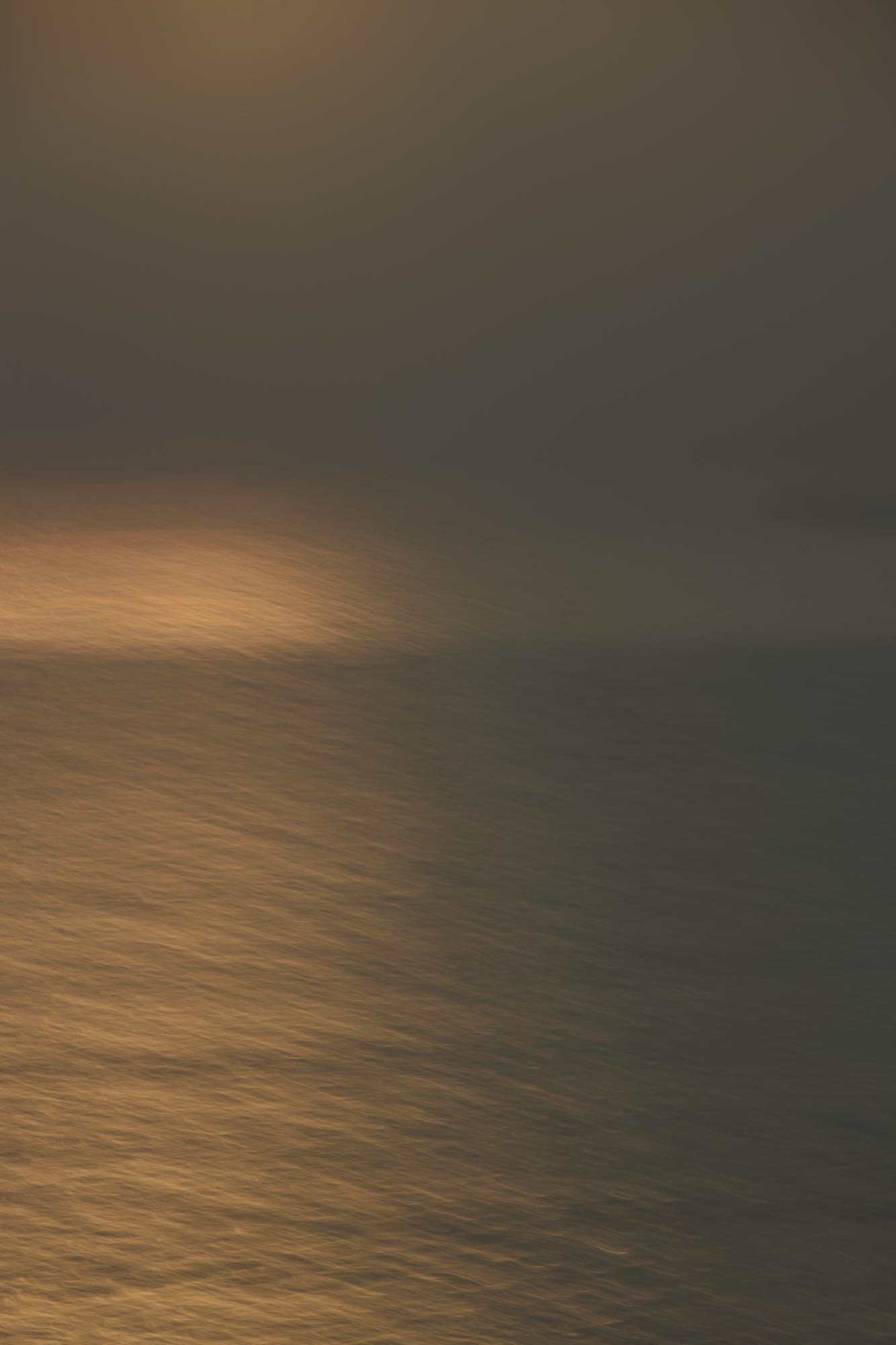

Oltre l'Acqua DUE, 2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

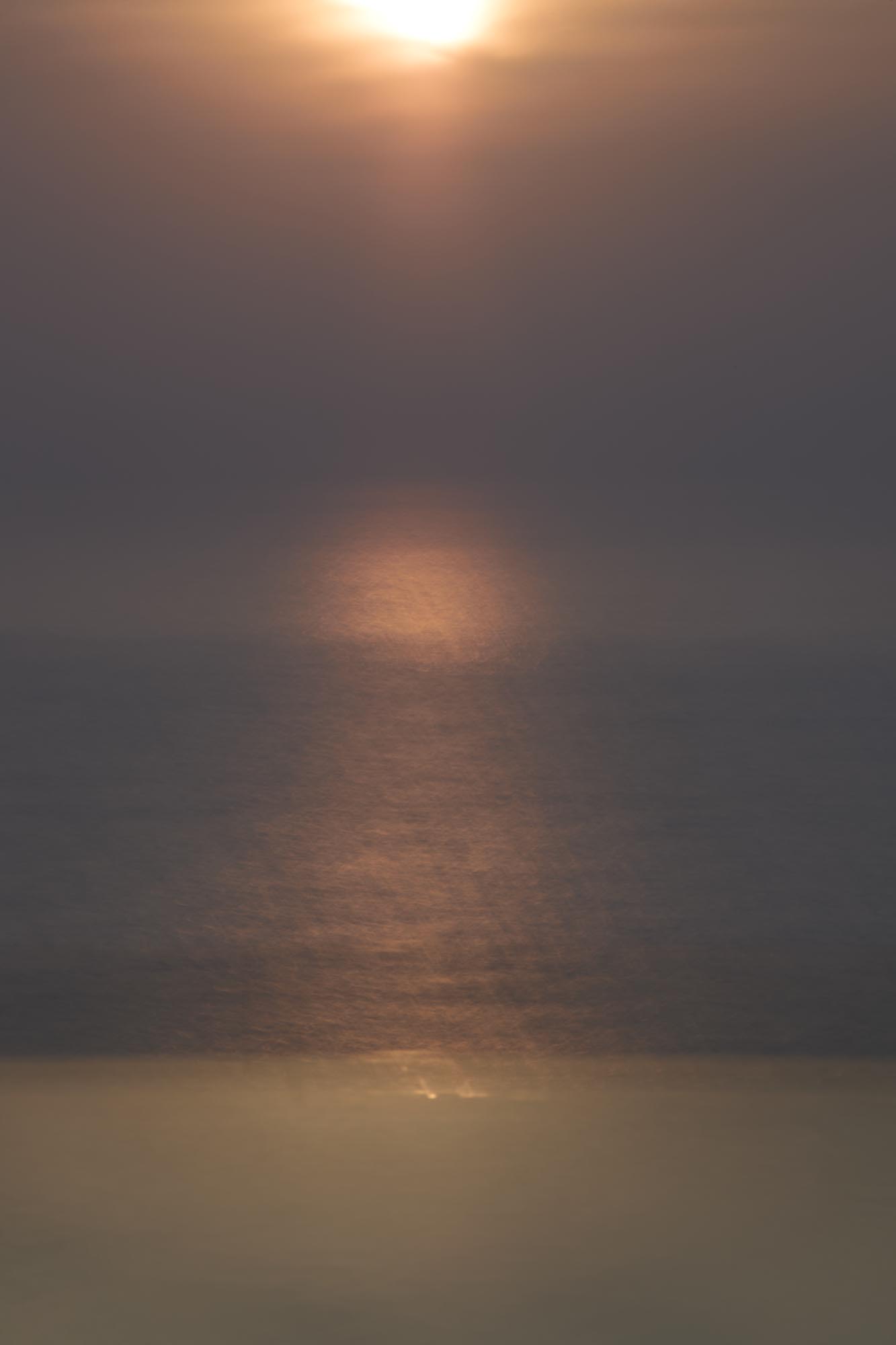

2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 150x100 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

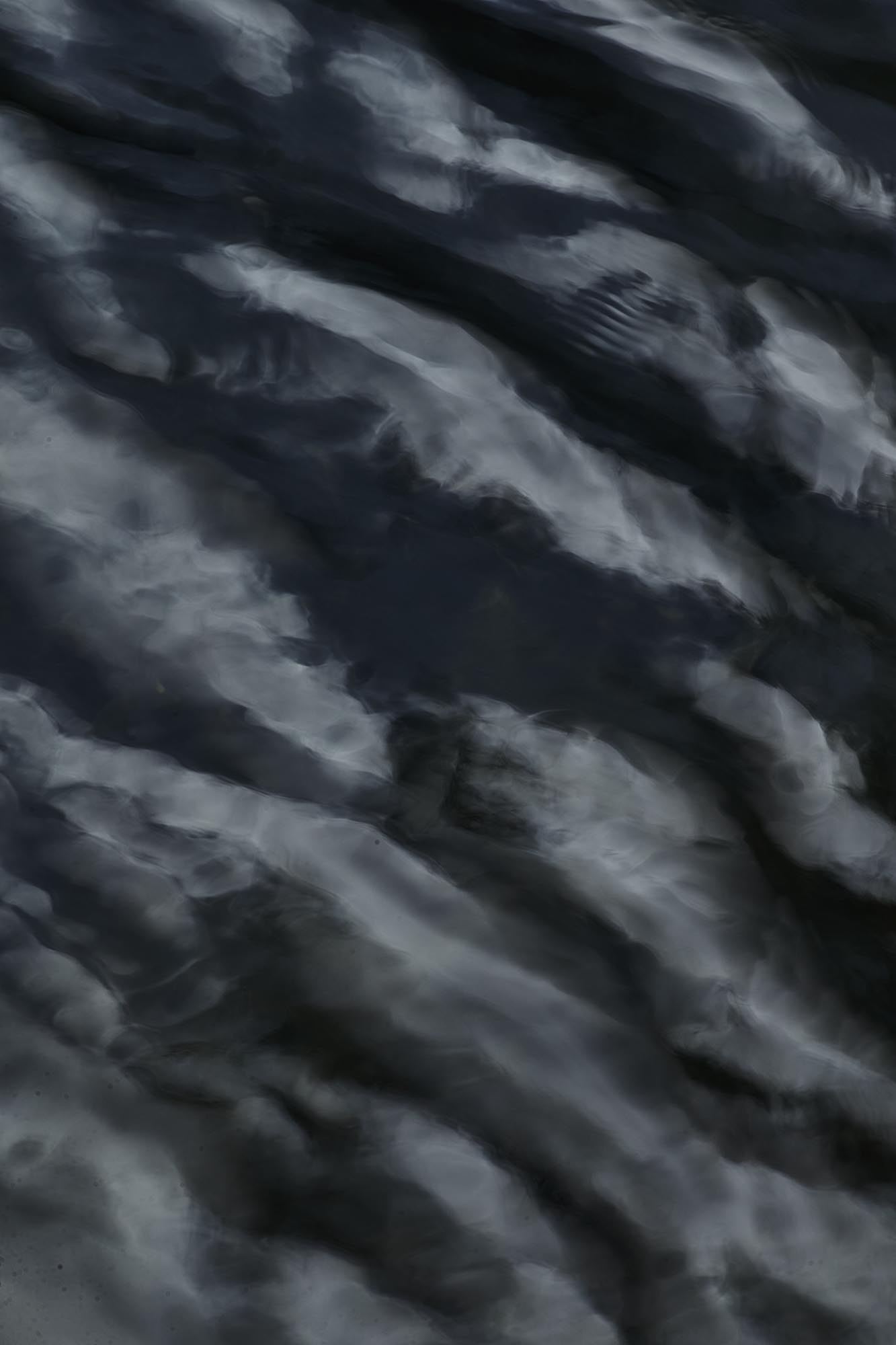

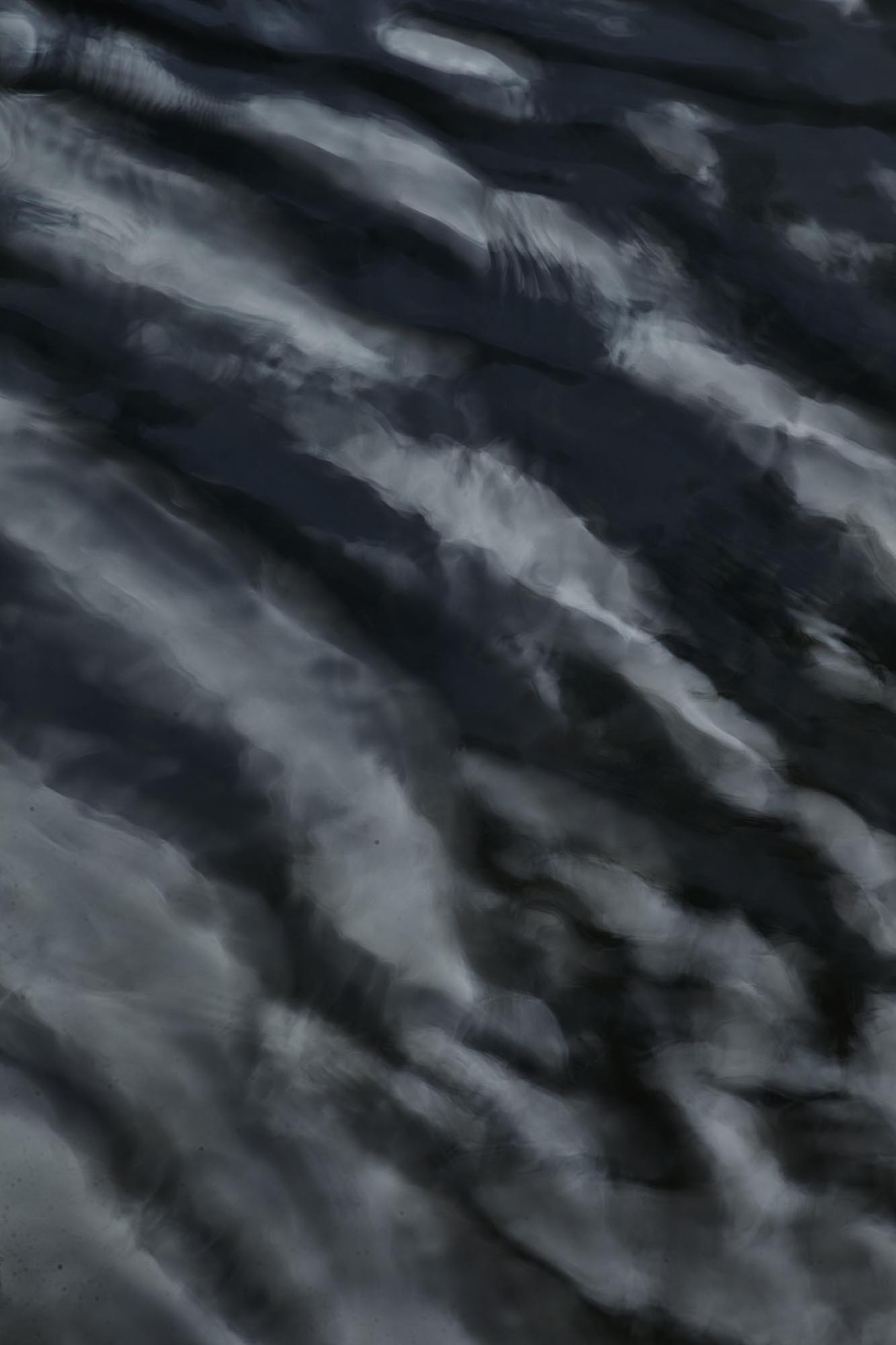

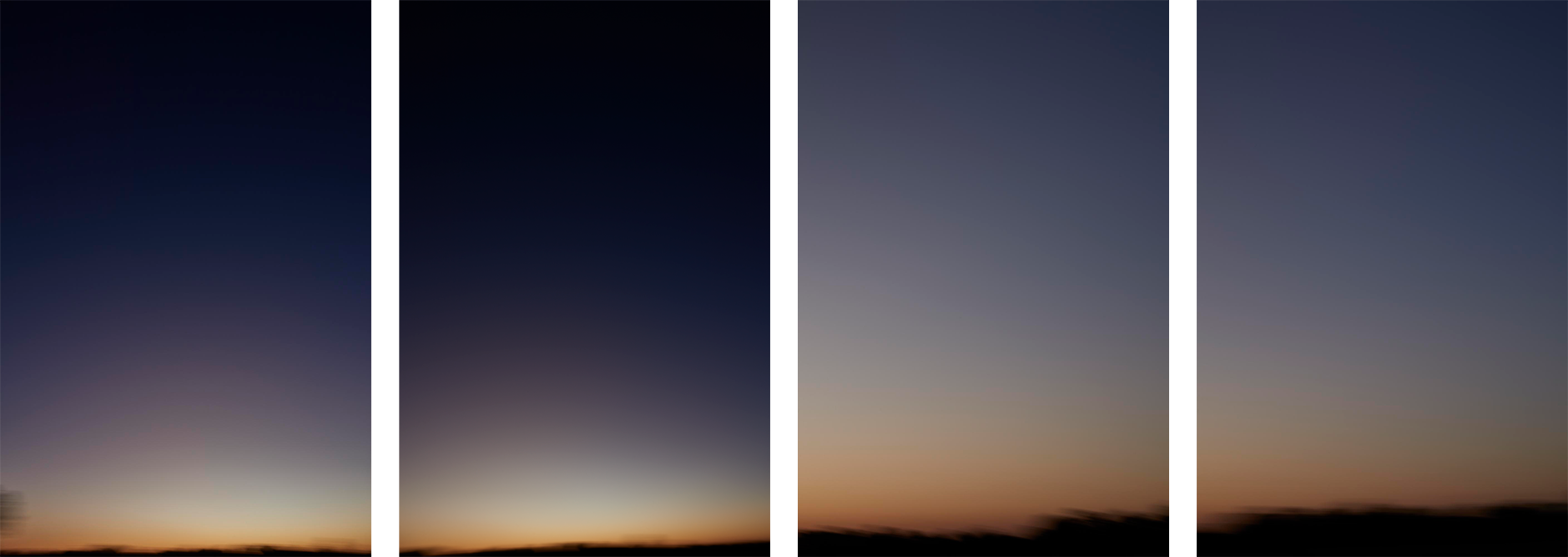

Untitled Quadrittico, 2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 45x30 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Untitled Trittico, 2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 45x30 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 45x30 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2024, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 45x30 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Attimi Sciolti, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Luce di Confine, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Codice di Luce, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Svanire, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Echi d'infinito, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Onde di Fuoco, 2020, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Orizzonte sfumato, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Echi di Tramonto, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Attraverso il Liquido , 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Trame d’Acqua, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Etereo Atlantico UNO, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Etereo Atlantico DUE, 2017, Stampa su Carta Fine Art, 100x150 cm, ED.1/9+2PA

Andante con Moto by Milovan Farronato When engaging with Veronica Gaido’s photographic work, I can’t help thinking about set theory, that field of mathematics dedicated to studying groups, or sets, of objects that share certain properties. Much like mathematical sets, Gaido’s work unfolds through intriguing intersections of constants and variables. Some features remain unchanged, defining her entire body of work and harmonizing its visual language. Other elements, however, bring uniqueness to each project, while recurring themes reappear in disguise — transformed yet still recognizable. Within her system, repetition is never identical; instead, it evolves, as if each image holds the memory of those that came before and a premonition of those yet to come.They are figurative works that possess a deep, unconscious memory with the ability to craft perfect constructions of interspersed light and movement, forming a perpetual balance between the stability of form and the uncertainty of change. Movement is an underlying theme, as in musical compositions in which motion is urged by the expression “andante con moto”. Her serial approach, her lengthy contemplations, and her refusal to maintain conventional distinctions between surrounding environment and subject-matter (the way she refrains from the creation of any visual hierarchy) are the three constants that never change. The image is always somehow, and for some reason, caught up in its context and its own motion. But are these actions or gestures? Behind an action lies a purpose, a reason, which is not necessarily or intrinsically found in a gesture. It could be argued that Gaido’s actions drive the gestures of her images, whether they depict a naked body or fading architecture. As if the intention were to lose intention, as if Gaido wanted to lead us off the path, to a place that celebrates pure gesture, gestures without purpose, involuntary gestures. Another, less obvious, constant is that each of her images can always be linked to one of the four primordial elements — those fundamental forces governing nature. None are exempt from this instinctive association or able to escape this calling, even when they verge on abstraction, dissolving into the air. Architecture, for example, is either liquid or fiery, there is no other possibility. The cathedral of Milan presents a blazing fire in every shot, a contained hearth in which flames dance. Mare Alchemico, meanwhile, reveals a bewitching pattern in which the motion of the waves becomes as hypnotic as the ripples of a sand dune. I can’t help but wonder if the unconsciousness of one element is intrinsically linked to the other! Where else could the earth be found (barely contained) than in the flesh of all those bodies embracing each other, trying to find their way around one another, expanding beyond their own skin, exploring new points of contact, longing for secret encounters. Of course, they transmit the feverish sensations of a warm, dusky light, nearing darkness, but they remain flesh, captured in their current state. They are tumultuous, trembling, segmented presences, yet deeply anchored to matter. Their flesh becomes the barrier that prevents the image from dissolving entirely into abstraction. It is no coincidence that bodily existence emerges more frequently in relationships between two figures rather than in solitude. Through these encounters, contacts, and bonds between bodies, her photography anchors itself to the earth, creating a moment of solidity in an otherwise impalpable visual universe. Water is omnipresent, it is the element that dominates the scene. Its fluidity is an aesthetic quality that transforms any subject, whatever it is, into an elusive, shifting entity. For example, in her images, Venice twists and folds like a sheet of paper moved by the wind, dissolving the rigidity of the architecture into a continuous, flowing movement. But this liquefaction is not limited to reflections in the water, even cities, like New York become dynamic, forming recurrent patterns and motifs that are repeated again and again until they vanish, within the limits imposed by the resolution of the image and the observer’s ability to engage with it. Like an engraved band encircling a body, her photography weaves an armour of images — a covering that both protects and exposes its wearer — within a system of signs where each element finds its place in an ever-changing whole. And it is precisely this tension between constant and variable, between form and dissolution, presence and movement, that reveals the power of her vision, beyond the image. Her intention is not to document, but to broaden perception, inviting the observer to go beyond the boundaries of representation and immerse themselves in a broader, more fluid dimension. Architecture is transformed into infinite textures, the landscapes before her dissolve into luminous folds, and bodies resonate with an unpredictable force. If the constants form Veronica Gaido’s visual grammar, what are the variables that give each image its uniqueness? If everything is always in motion, what makes every work of art unique? The changing light, for one thing. No longer simply a reflection, light becomes an architectural element, the backbone of a city seemingly built on air, dematerialised by the heat. And then there is the rhythm of each composition, the syncopated fragments and the visual beats pulsing through a city that knows no peace. Lastly, there is the density of the darkness, which is not simply an absence of light, but an absolute presence, an element with the same power to create form as the fiercest light. Each work is distinguished by the particular element fuelling it, the vibe, the pace, the flow. Amidst this constant transformation, the true essence of the work emerges, revealing a process that seeks not an end point but the continuous possibility of change.

Andante con Moto di Milovan Farronato Di fronte all’opera fotografica di Veronica Gaido non posso far a meno di pensare all’insiemistica, ovvero a quel ramo della matematica impegnata a studiare le collezioni di oggetti che condividono determinate proprietà. Anche il lavoro di Gaido si articola nell’avvincente danza tra costanti e variabili: ci sono presenze immutabili che definisco la specie — armonizzando il linguaggio visivo — e poi ci sono gli elementi che offrono specificità a ogni progetto, e poi ancora quelli che si rincorrono e si ripresentano sotto mentite spoglie, trasformati e tuttavia riconoscibili. È un sistema, il suo, in cui la ripetizione non è mai identica a se stessa, ma si evolve, come se ogni immagine contenesse la memoria di quelle che l’hanno preceduta e l’intuizione di quelle che la seguiranno. Sono figurazione che possiedono una profonda memoria inconscia che sa edificare strutture perfette fatte di intarsi di luce e movimento, perennemente in bilico tra la stabilità della forma e l’instabilità del divenire. Il movimento è un principio cardine, un “andante con moto”. L’approccio seriale, le lunghe esposizioni e il superamento della tradizionale distinzione tra ambiente circostante e soggetto — ovvero l’eliminazione di una gerarchia visiva — sono le tre costanti che non cambiano mai. L’immagine è sempre in qualche modo, e per qualche motivo impigliata nel contesto a cui appartiene e nello spostamento che compie. Ma si tratta di azioni o di gesti? Il primo prevede una finalità, il secondo invece non la ritiene necessaria per la sua intrinseca natura. Si potrebbe sostenere che le azioni di Gaido muovono la gestualità delle sue immagini, sia che si tratta di un corpo nudo che di un’architettura in dissolvenza. Come se l’intenzione fosse quella di perdere intenzione, come se Gaido ci volesse guidare fuori dal sentiero, in un luogo che celebra il gesto puro senza scopo, involontario. Un’altra costante, meno evidente, è che ogni sua immagine può essere ricondotta sempre e comunque a uno dei quattro elementi primordiali, a quelle essenze fondamentali che governano la natura. Nessuna è esente da questa istintiva associazione o si può sottrarre a questo richiamo anche quando tendono maggiormente all’astrazione, e quindi a volare via, nell’aria. Le architetture, ad esempio sono o liquide o infuocate, non c’è altra possibilità. Il Duomo di Milano è un incendio che divampa in ogni inquadratura, un focolare ordinato, ma guizzante. Il Mare Alchemico è invece un pattern in cui la malia delle onde diventa ipnotica come anse di una duna di sabbia. Mi viene quasi il sospetto che l’inconscio di un elemento implichi l’altro! Dove potrebbe stare la terra se non trattenuta a stento nella carne di tutti quei corpi che si abbracciano, che tentano di circumnavigarsi, che si spingono oltre la propria pelle sperimentando inediti punti di tangenza, bramando incontri clandestini. Certo, anche loro trasmettono il febbrile sentire di una luce calda, crepuscolare, che sfiora il tenebrore, ma restano carne ancorata alla loro datità. Sono presenze tumultuose, tremolanti, segmentate, eppure profondamente ancorate alla materia. La carne diventa il punto di resistenza, l’elemento che impedisce alla visione di dissolversi completamente nell’astrazione. Non è un caso che la corporeità emerga più frequentemente nella relazione tra due figure piuttosto che nella solitudine. L’incontro, il contatto, la legatura tra i corpi diventa il modo in cui la fotografia si ancora alla terra, creando un momento di solidità in un universo visivo altrimenti impalpabile. L’acqua certo è onnipresente, è l’elemento che domina la scena. La sua fluidità è un principio estetico, una qualità che trasforma ogni soggetto in un’entità cangiante e sfuggente. Venezia, ad esempio, nelle sue immagini si piega e si accartoccia come un foglio mosso dal vento, dissolvendo la rigidità dell’architettura in un ritmo liquido e continuo. Ma è una liquefazione che non si limita al riflesso dell’acqua: anche le città, come New York, diventano pattern dinamici, schemi che si ripetono fino a dissolversi nel limite imposto dalla risoluzione dell’immagine e dalla capacità dello spettatore di contenere la visione. Come un intarsio che cinge il corpo, la sua fotografia costruisce un’armatura di immagini che protegge e al tempo stesso espone, un sistema di segni in cui ogni elemento trova il proprio posto in un insieme in continua trasformazione. E proprio in questa tensione tra costante e variabile, tra forma e dissoluzione, tra presenza e movimento, si manifesta la potenza del suo sguardo che va oltre l’immagine. Non intende documentare, ma espandere la percezione, invitando lo spettatore a superare i confini della rappresentazione e a immergersi in una dimensione più ampia, più fluida. Le architetture si trasformano in trame infinite, i suoi paesaggi si dissolvono in pieghe luminose, i suoi corpi vibrano di una presenza instabile. Se le costanti definiscono la grammatica visiva di Veronica Gaido, quali sono le variabili che danno a ogni immagine la propria unicità? Se tutto è in movimento, cosa rende ogni opera irripetibile? Sono le qualità mutevoli della luce, che non è più solo riflesso ma sostanza architettonica, colonna portante di una città che sembra costruita sull’aria, quasi smaterializzata dal calore. Sono i ritmi interni di ogni composizione che diventano frammenti sincopati, battiti visivi che si rincorrono in una città che non conosce quiete. È la densità del buio, che non è semplice assenza di luce, ma presenza assoluta, capace di scolpire i volumi con la stessa forza delle illuminazioni più violente. Ogni opera si distingue per l’elemento che la anima: la vibrazione che la percorre, il tempo che la governa, la forma in cui il movimento si deposita. In questa costante mutazione si manifesta la vera essenza del lavoro: un processo che non cerca un punto fermo, ma la continua possibilità di transizione.

Veronica Gaido - Photographer